Born in 1921 as Charles Dennis Buchinsky, Bronson had a difficult journey and childhood in particular, growing up in a coal mining town in Croyle Township, about 60 miles from Pittsburgh.

He experienced childhood alongside another 14 siblings, coming in at 9th out of the total 15. While everyone knows just how expensive a single child could be, just imagine the pressure when the family is dirt poor. This was exactly the case for Bronson.

Bronson and the massive family lived in a small, company-built shack just a few yards from the coal car tracks. The house was completely inadequate to house such a large family: it was so small, they had to take turns sleeping.

“There was no love in my house,” he said. “The only physical contact I had with my mother was when she took me between her knees to pull the lice out of my hair.”

Dire Beginnings

But it wasn’t just the Bronson family who had it bad: the entire town was a rather miserable and hopeless place, serving only company officials who wanted to facilitate the coal mining and maximize profits.

There was little nature, the drinking water was sub-par, and prospects were dark. It’s no surprise then that Bronson has described his childhood as lonely and unhappy.

Things got increasingly difficult around the time Bronson was a teenager and his father passed away. While he was already used to haggling for small change, he now had to quit school to support his family. Naturally, this could only mean one thing: getting a job as a coal miner.

Memories of this phase of his life haunted Bronson well into adulthood, with him never forgetting the backbreaking work or the powerful smell of coal in his nostrils. Bronson felt that he was living on his hands and knees, breathing black dust.

He has often also vividly recalled the many headaches that mining work gave him, and how his hands were always rough and dirty. Bronson has said that he felt he was born with a shovel in his mouth, not a spoon.

But above the physical impacts was an even more profound psychological one: his days working as a coal miner gave him a profound inferiority complex.

“During my years as a miner, I was just a kid, but I was convinced that I was the lowliest of all forms of man,” he said.

In fact, according to Bronson, all of the coal miners in his town had the same complex: railroad and steelworkers were seen as the ‘elite’ while they were perceived as the lowliest form of man.

“Very few people know what it is like to live down there underneath the surface of the world, in that total blackness.”

When he was finally drafted into the army, he was thrilled. He could at last escape his dark world and expect to be well-fed and well-dressed. It’s this period of his life that would ultimately open up the doors to Bronson becoming one of the most iconic names in Hollywood.

A Bright New Path

After serving in World War II, Bronson returned to the U.S. and began to study art before enrolling at the Pasadena Playhouse in California.

His skills and talents were almost immediately clear: one teacher noticed them early on and soon referred the young Bronson to director Henry Hathaway. This eventually resulted in him being cast in his very first film: the 1951 You’re in the Navy Now.

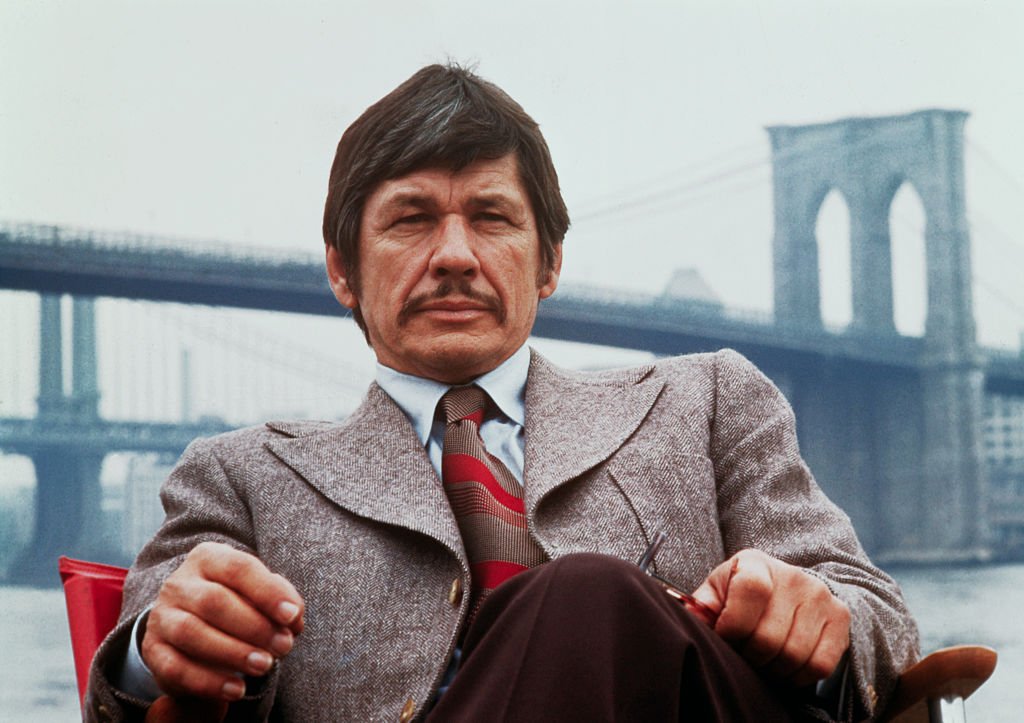

While his early work often saw him uncredited, by 1954 he was acclaimed by critics for his work in Vera Cruz, and, four years later, as a lead in Machine-Gun Kelly.

Early on, Bronson substituted his acting work with work as a bricklayer, cook, onion-picker, and painter. He also officially changed his name from Buchinsky to Bronson in the 1950s, worried that his Russian-sounding name wouldn’t be well-received during the very anti-Communist era.

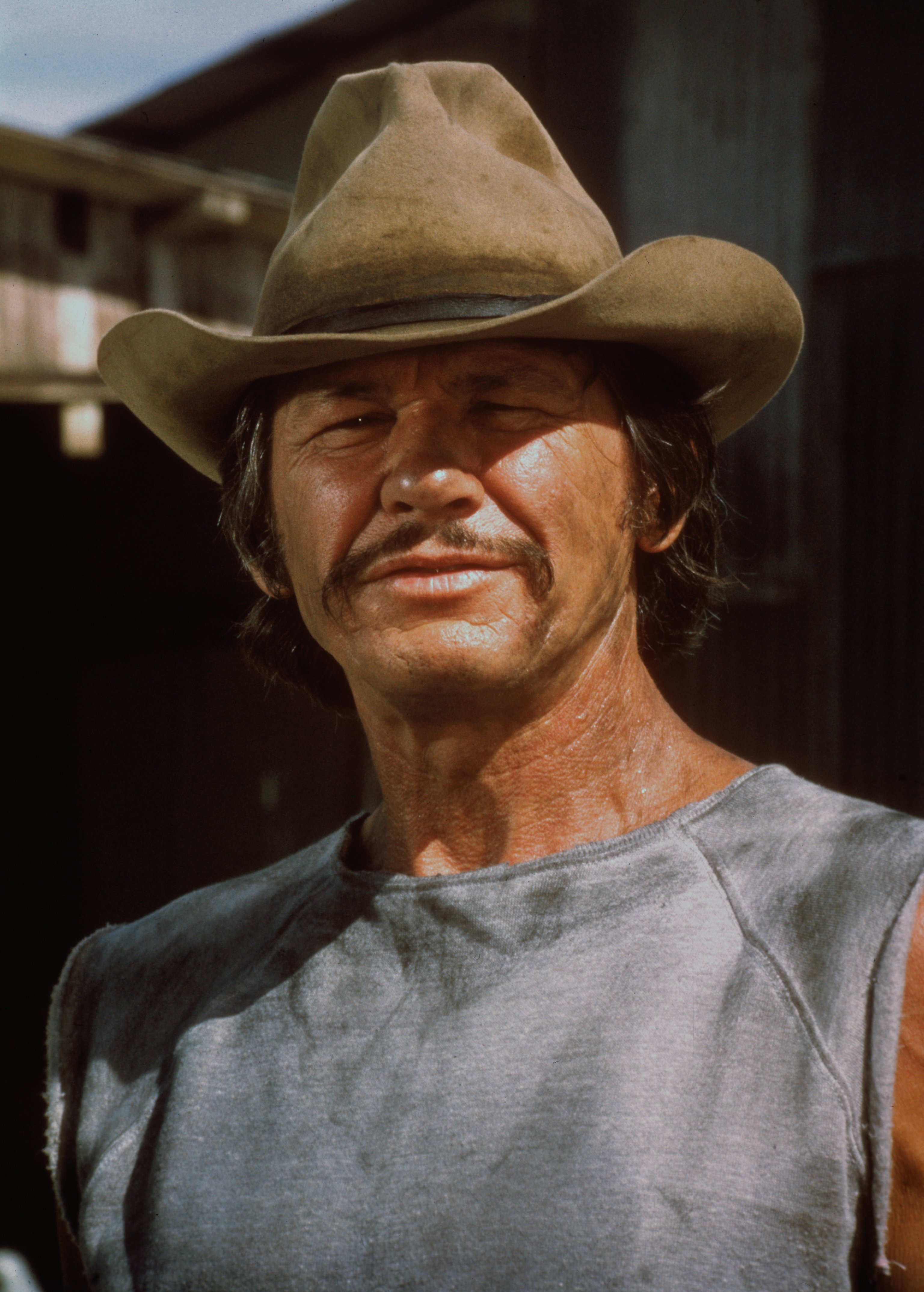

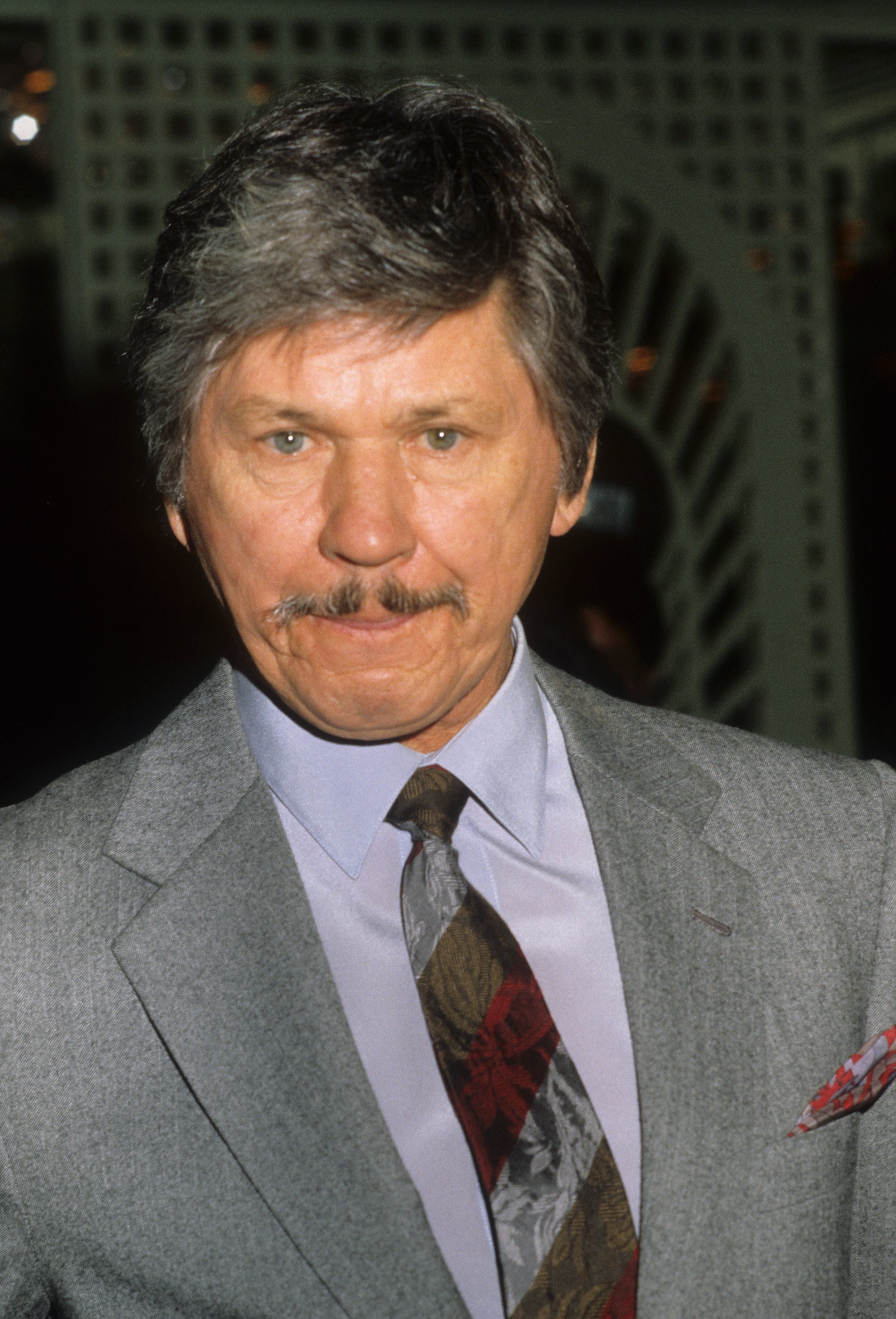

But it wasn’t until 1974 that he landed his breakthrough role as Paul Kersey, an architect who becomes a vigilante after his wife and daughter are attacked in Death Wish. The movie’s popularity led to several sequels to be produced over the next decades.

Bronson further rose to stardom in 1975, after starring as the legendary drifter James Coburn in Hard Times.

It took time to adjust to his stardom, and Bronson is reported to have been haunted by his dark childhood.

According to co-star Andrew Stevens, he particularly avoided people who were intrusive or came across to him as threatening. On the other hand, when feeling comfortable and at ease, Bronson was known to be open, charming, and funny.

Life of an Icon

Bronson married three times: first to Harriet Tendler between 1949 and 1965, with whom he had two children.

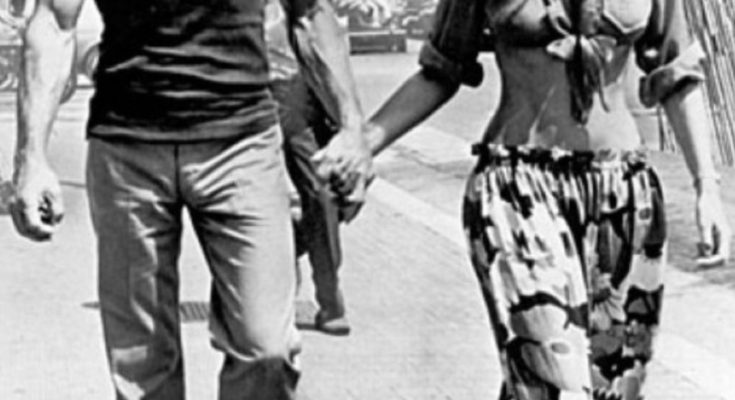

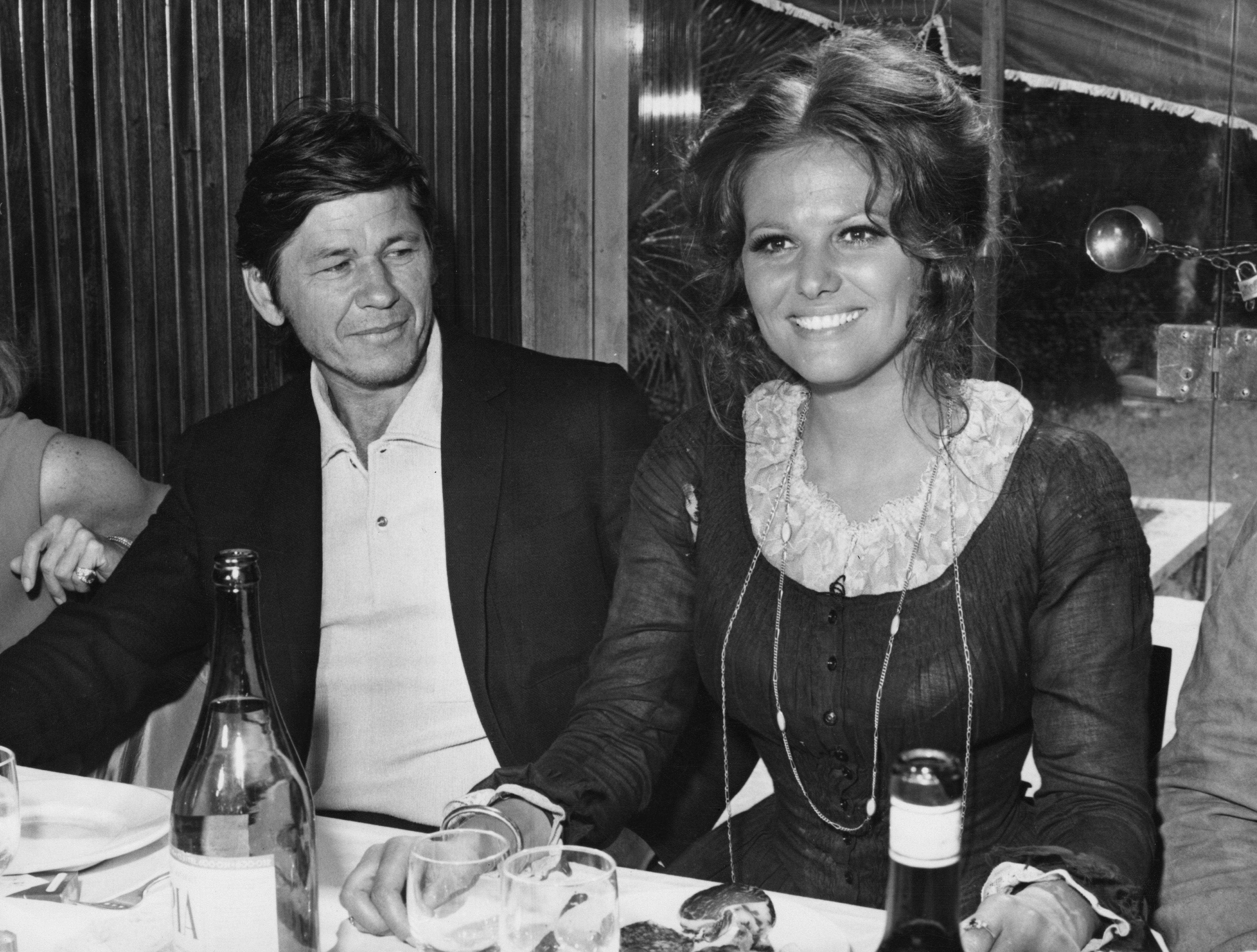

His second wife was the popular British actress, Jill Ireland, who co-starred with Bronson in a total 15 films, including The Valachi Papers and Love and Bullets. They had two children together, but Ireland tragically died in 1990 after a battle with cancer.

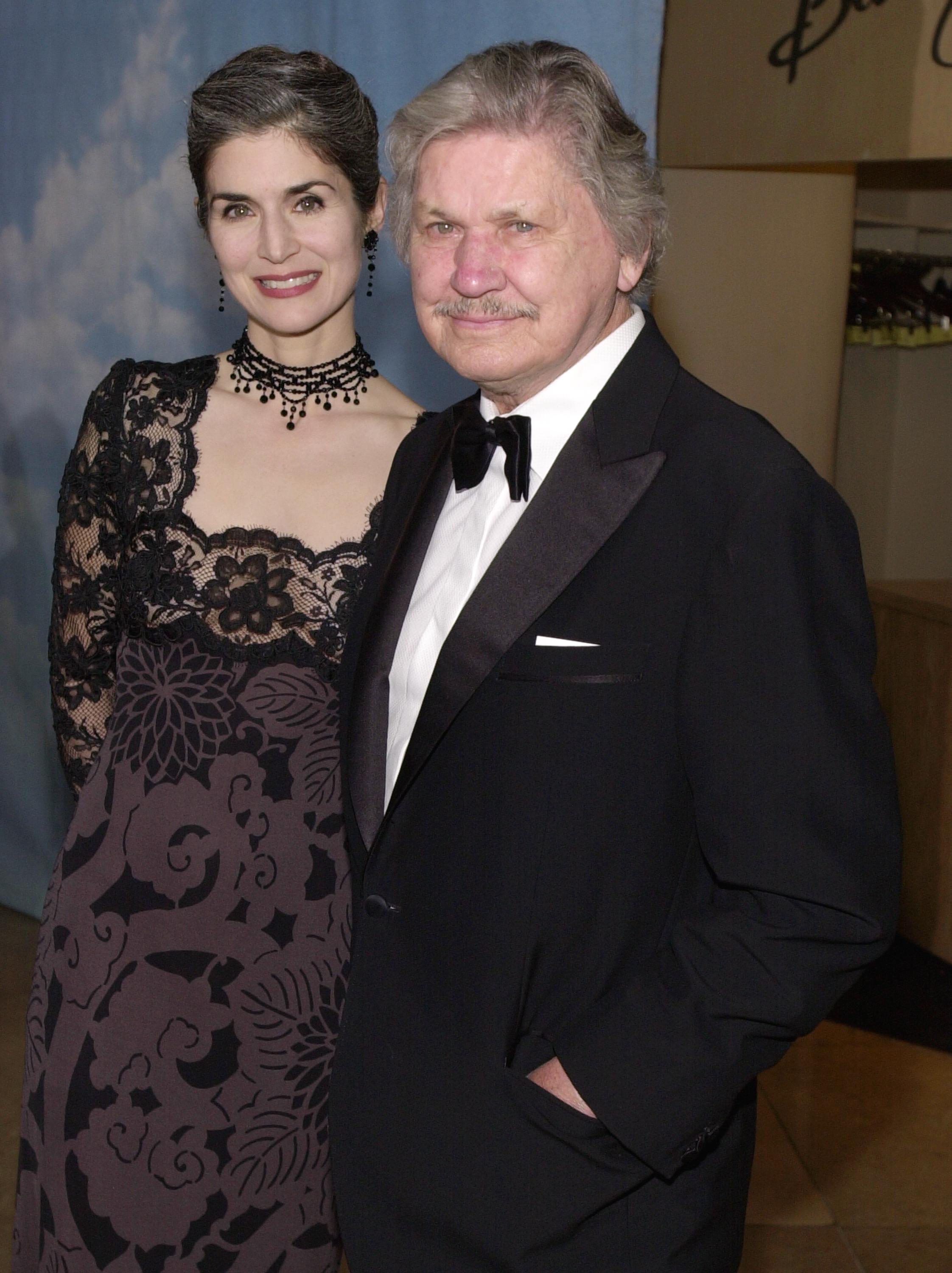

In December 1998, Bronson entered his third marriage with Kim Weeks, a former employee of an audiobook company who had helped record Ireland’s audiobooks.

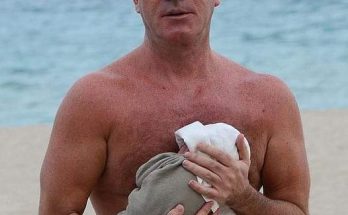

Later in life, Bronson was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. His battle with the illness was described as a “stark contrast to the high-octane vitality of his incredible life.”

The star was sometimes spotted shambled and dazed around Beverly Hills. Luckily, wife Weeks was around to care for the ageing actor.

“The family has known for almost a year that something was wrong because Charles just hasn’t been himself,” his sister, Catherine Pidgeon, said.

According to Pidgeon, Bronson had begun to speak more slowly and was slurring his words, but could still recognize his family and managed to spend Christmas 2001 with them.

Bronson was hit with a bout of pneumonia which caused his health to quickly decline over just a few weeks. He died on August 30, 2003 at age 81 at Cedars-Sinai hospital in Los Angeles, survived by his wife, Kim, three daughters, Suzanne, Katrina Holden-Bronson, and Zuleika, a son, two stepsons, Paul and Valentine McCallum, and two grandchildren.