Starship Troopers, Road House, Robocop… it’s likely these films don’t bring to mind the phrase “deadpan satire,” but they should. Some of the most brilliant satirical films of the last five decades aren’t the kind of pictures audiences view as intellectual think pieces, because any writer and director worth her salt knows satire is not broad comedy, like parody, but rather an act of becoming the thing you wish to critique and taking it apart from the inside. Many of these movies are couched in the language of tentpole productions, as a way to quietly communicate with the masses.

Some of these films work better than others, but that’s not to say any are bad; some were simply trying to do too much too soon. For instance, 1974’s Death Race 2000 predicted the 21st century’s preoccupation with audiences voting for the onscreen pain of contestants, but we’re just now figuring out how accurate and insightful those predictions are, from a film many dismiss as exploitative nonsense. With others, it’s possible the people making them didn’t even realize their brilliant meta commentaries themselves.

The best self-aware movie satires barely even acknowledge that they’re satires, instead choosing to lean into their genre and let the audience figure it out. Directors like Paul Verhoeven and Brian De Palma have made entire careers out of making films that perfectly play into their audience’s sensibilities, while also saying something about the people who paid to see the film and the world around them. Those two maestros have plenty of thoughtful contemporaries in horror, a genre full of movies that aren’t about what they seem to be about on the surface.

If you’re confused about what all this means, take a look at this collection of movies you thought were stupid but are secretly brilliant, films that are trying to do something more than genre trappings will allow.

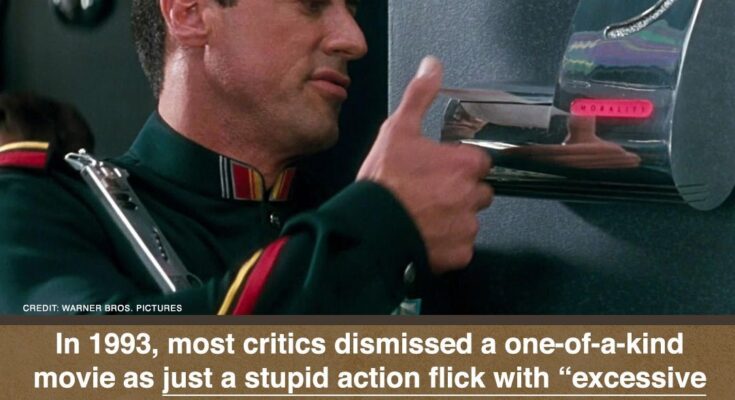

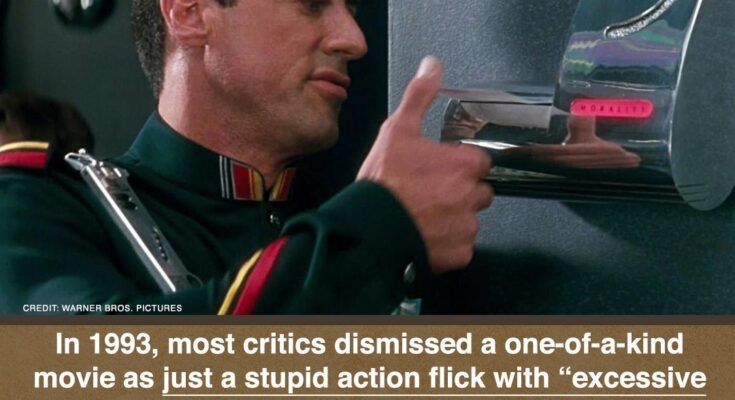

Demolition Man

Photo: Warner Bros

Demolition Man doesn’t have much of a reputation in the 21st century. It was advertised as a straight up, muscle bound throwdown between mega stars Sylvester Stallone and Wesley Snipes upon its release in 1993, yet some critics recognized bits and pieces of satire piercing the veneer of masculine bravado. As Richard Schickel wrote in Time, “Some sharp social satire is almost undermined by excessive explosions and careless casting.” Writing in The New York Times, Vincent Canby derided the movie as an anti-PC desire to return to the rapey idiocy of the Reagan years.

Of course, hindsight is 20/20, and it’s now safe to say Demolition Man is a genius satire with perfect casting. Wesley Snipes plays the antagonist with vaudevillian relish, while casting Stallone as a 20th century Neanderthal struggling to adapt to a socialist utopia is an incisive commentary on America and our taste for violence, stupidity, and perversion. Hell, his character’s name is John Spartan, a combination of the most American of white American names (John) and a culture of ancient, homoerotic warriors (Sparta). Sandra Bullock is in the mix, too, as Huxley (Aldous reference!), a future cop assigned to hang out with Stallone.

Yet Demolition Man is far from a simple send up of classic American masculinity and Old West chaos rules. It takes its utopian peaceful PC society to task as much as it points out how unsustainable the opposite is. It’s impossible to prevent malice from manifesting, and new speak oppression hardly helps matters. Violence is wrong, as is robbing people of the free will that begets violence. Perhaps more than anything else, Demolition Man is a conflicted, gleeful, nihilist manifesto. it also cannily played to increasing corporate ubiquity (all restaurants are Taco Bell following the “franchise wars”), “wellness obsession,” and the escalating hysteria over “cancel culture” decades later.