Ulysses, Kansas – Born Twice and Still Kickin!

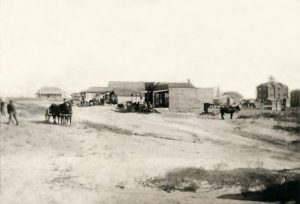

Ulysses was born twice along the Cimarron Branch of the old Santa Fe Trail in Grant County, Kansas. The first time was in 1885 when it was founded, and then a second time when the entire town was loaded onto skids and moved three miles across the prairie.

Ulysses was established on March 20, 1873, when the Santa Fe Trail traffic was beginning to slow down due to the steam engine coming to western Kansas. But, the steam engine led to several towns springing up in Grant County, including Appomattox, Golden, Shockey, Zionville, and several other now Extinct Towns. At one time, there were some 20 different post offices in Grant County; however, all of the post offices except for Ulysses are now gone. The only other remaining towns are the tiny little unincorporated burgs of Hickok and Ryus.

The town was named for General Ulysses S. Grant, and the settlement was surveyed by George Washington Earp, first cousin to Wyatt Earp of Dodge City and Tombstone fame, in 1885. Earp was one of Ulysses’ first promoters, a businessman, and, like his cousins, its first peace officer. Furthermore, according to legend, he was just as “free with his gun” as Wyatt and his bunch.

George Washington Earp

By 1886, the town boasted nearly 1,500 people, an opera house, a large hotel, several other businesses, and six saloons, even though Kansas was considered a dry state at the time. Two years later, it had added 500 residents, two more hotels, and supported 12 restaurants.

When Grant County was first established in 1887, there were two candidates for the county seat — Ulysses and Tilden (later called Appomattox.) The governor’s proclamation was not made until June 1888, at which time named Ulysses as the temporary county seat and appointed County Officers.

A few months later, an election was held to determine the permanent location of the county seat on October 16, 1888. Before and after the election, the two towns were embroiled and a fierce county seat war.

Constable George Earp would later say that the Ulysses Town Company imported several noted gunmen “to protect the security of the ballot” at the elections. Among them were Bat Masterson, Luke Short, Ed Dlathe, Jim Drury, Bill Wells, and Ed Short. The men built a lumber barricade across the street from the polling place, stationing themselves behind it with their Winchesters and six-shooters in case of trouble or an attempt to steal the ballot box. But, no trouble erupted, and in the end, the election resulted in a win for Ulysses.

But, like many other Kansas Counties, the fight wouldn’t end there. With corruption charges, the fight went to the Kansas Supreme Court, where evidence was submitted by a Tilden partisan named Alvin Campbell. He introduced facts to show that the city council of Ulysses had bonded the people to $36,000 to buy votes, claiming that the total votes paid for were 388.

It was an “open secret” that votes were bought, and “professional voters” had been brought in and boarded for the requisite 30 days before the election and given $10 each when they had voted. But, it was not known at the time that this had been done at public expense. It was also alleged that “professional toughs” were hired to intimidate the Tilden voters.

The exposure of the fact that public funds had been used created excitement among the citizens of the county, who found themselves subject to the payment of bonds, and those to blame for the outrage retaliated upon Alvin Campbell by tarring him in August 1889.

It was also shown in court that Tilden had bought votes and engaged in irregular practices, and though Ulysses finally won, it was a dearly bought victory. Added to the $36,000 spent in the county seat fight was $13,000 in bonds, which had been voted for a schoolhouse, and $8,000 for a courthouse. Ulysses has since retained its county seat status.

At the height of the county seat contest between Ulysses and Appomattox in 1888, Ulysses boasted a population of 2,000 and supported 12 restaurants, four hotels, several other businesses, six gambling houses, and twelve saloons.

Though she finally won the honor of county seat, the town went deeply into debt winning the title. In 1909, when Ulysses could not climb out of its profound financial burden and prevent foreclosure of the entire townsite, the community just decided to move. Loading every building onto skids, the townspeople relocated three miles across the prairie to the present-day site of Ulysses. All the lots in the old town were deeded back to the East Coast bondholders, and only a masonry school was left behind.

But the troubles weren’t over. In 1898, the county suffered from severe crop failure causing panic and reducing the population from 1,500 to 400 in Ulysses, and later only to some 40 souls. Buildings were moved away, banks closed, and merchants let their stock of goods run down.

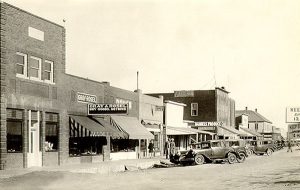

The “new” town was officially called “New Ulysses,” and the old site was referred to as “Old Ulysses.” The Hotel Edwards had to be cut into three sections for moving. Today, it is the only remaining business building moved from the old town that still exists. It now rests on the Grant County Museum grounds, restored to its original appearance.

“Old Ulysses” was located about three miles east of Ulysses on U.S. Highway 160. The site is now on private property.

In the 1920s, natural gas was discovered in the area surrounding Ulysses. The Hugoton natural gas field called “The Gas Capital of the United States” spans over 4,800 square miles. This discovery led to a strong area of prosperity.

In 1921, the town name was officially changed to “Ulysses” rather than “New Ulysses.”

Today, a portion of the Ulysses high school grounds is on the old site of Appomattox. Part of the old Hotel Edwards is a feature of the local museum, and history abounds at nearby Wagon Bed Spring, south of town.

The vast plains that surround Ulysses afford the most spectacular sunrises and sunsets that one has ever seen. For the hunting enthusiast, the area is renowned for its excellent deer and pheasant hunting.

The Cimarron Cutoff on the Santa Fe Trail passed just east of the current site of Ulysses, turned south, and crossed the path of current highway US 160 following the Cimarron River.

The famous watering spot along the Santa Fe Trail, Wagon Bed Spring, is located ten miles south of Ulysses. The Cimarron cutoff was a risk to those early travelers, as the journey was periled with dry creek beds and frequent Indian attacks. However, many were willing to take the risk to save hundreds of miles of travel rather than taking the “safer” trail through Colorado. The “La Jornada,” as the dry crossing between the Cimarron and the Arkansas Rivers became known, was the shortest road from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, to the Southwest. Near here, noted Western explorer and fur trader Jedediah Smith spent four days without water and was killed by Comanche Indians just as he reached the river.

Though no military post was ever established at Wagon Bed Spring, hundreds of soldiers refreshed themselves there from the start of the Mexican-American War in 1846 until the railroads replaced the wagon road.

1864 was the bloodiest year for Indian attacks all along the Santa Fe Trail, and 15 men were killed at Wagon Bed Spring during a two-week period. Soon, General James H. Carleton, commanding the Department of New Mexico, sent 100 men to Wagon Bed Spring with rations for sixty days. Today, the site still provides “treasure” hunters with caches of lead balls, empty cartridges, and arrowheads.

In 1961, Wagon Bed Spring was recognized as a National Historic Landmark. However, the spring itself is long dry from irrigating the fertile fields of western Kansas.

Ulysses is located in Grant County in southwest Kansas.